El Cerro Mission: The Place that Raised Me

A deep dive into a different kind of New Mexico, and where nothingness was never empty.

I wanted my first post to share who I am, and the place that raised me.

I grew up in El Cerro Mission. Since the early 1990s, Mexican immigrant families like mine began to settle in the area. East of the historic Tomé land grant, at the time, it represented new development. However, this was not like the resourced development on the west side of town, named after the city’s rich families, Huning Ranch.

Instead, El Cerro was like an undercommons1, a network that emerged from the edges of power. Closer to the border, the area would be called a colonia; a term to describe communities in the borderlands who lack basic civic infrastructure needs, like safe roads and trash service. But because El Cerro is more than 100 miles from the border with Mexico, it is just a poor neighborhood.

El Cerro wasn’t close to the border, but it was close to places like Belen, Tomé, Los Lunas, Bosque Farms, Peralta, and Meadowlake. As a kid, I associated Belen with Beall’s shopping trips with my mom. I thought of Tomé, Bosque Farms, Peralta, and Los Lunas as the places where the richer white people lived, with the rich Spanish white people there too. And Meadowlake made more sense to me, it was like my home, where the mostly Mexican immigrant families like my parents, los recién llegados, felt safe.

While I didn’t have this language at the time, as a young girl I intuitively knew that El Cerro wasn’t the New Mexico you find on postcards: the charming adobe houses, acequias, hornos, and ristras hanging on sturdy columns. It was the New Mexico of trailers, stray dogs, microwave dinners, and car decals on lifted trucks.

Families chose to live on unincorporated county land, where services like trash pickup weren’t commonplace. Growing up I remember seeing the same dirty mattresses and other discarded items left on the sides of roads for years.

Being neglected also means being less surveilled and policed. Driving on dirt roads with the same pot holes from decades ago, people steer their trucks, intuitively knowing which potholes and checkpoints to avoid. Despite being a dry, remote land, in El Cerro, families could build their own houses and plant their own trees and feel free.

My parents bought an acre of land and a trailer, with help from my dear tia. With their two young daughters, my older sister and I, Armando and Ruth built a home. For years, my dad built our house. I remember roller skating through the frame as he pointed out our future rooms, closets, bathrooms. I was five when we moved into the 3 bedroom family house lovingly built. The home they built stayed with me, even after life pulled them in different directions.

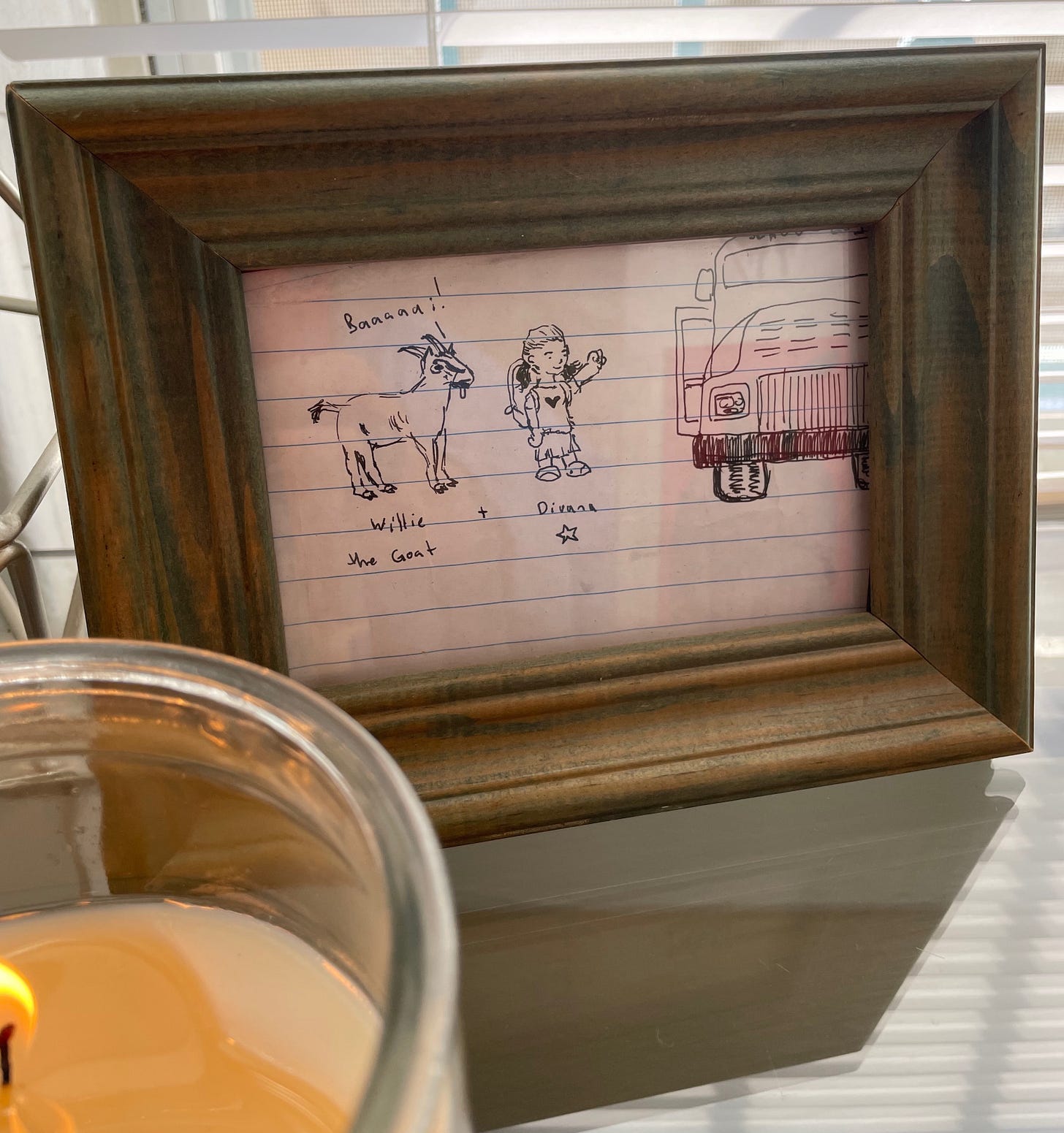

In El Cerro, I grew up surrounded by animals. There was Willie the goat, who, according to my dad, was my first best friend when I was about two to four years old. We were inseparable and he would even walk me to the preschool bus stop right in front of our house.

Later, there were dogs like Arno, who took over the job when I started elementary school, escorting me to the corner bus stop. We had horses that I only know from pictures and the occasional pig eventually slaughtered. In our backyard, my dad kept his roosters, the gallinero. And there were the ants who my dad kept as his own strange, fond pets.

I also grew up surrounded by wide open skies. I could enjoy them best as a young girl by climbing to the rooftop of my Papi’s gallinero. To get up there, I had to navigate my dad’s discarded tools; planks of wood littered with nails drilled in and no place to take hold. I knew which planks were sturdy enough to step on and use as leverage to climb the roof.

Up there, I felt free.

To the east were the Manzanos.

To the west was Tomé.

To the south, a scattering of trailers that gave way to what I once thought was nothingness.

To the north, more dirt roads and trailers, and then again the abrupt stop into what I could only name as empty.

I wonder now what it means that I grew up feeling free while being surrounded by what I called nothingness. Maybe it wasn’t nothing after all. Maybe it was distance. Breath. Life scattered across the desert, growing in its own way.

When I write about land and belonging now, I think about that childhood sense of freedom, and I think about how I am still learning to name what I thought I understood. El Cerro wasn’t empty. It was vast. It was alive.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Wivenhoe New York Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Your words are so moving! I am just now catching up on your posts and I love the way you write about your life. Keep going pre! ❤️